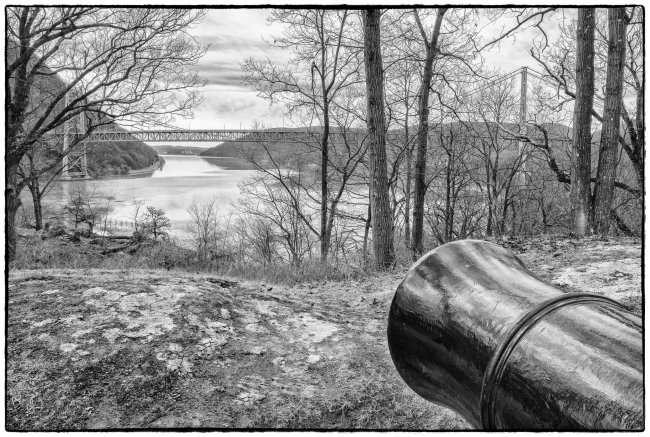

The scene of the bloody Battle of Fort Montgomery where Danforth won his freedom

By Mary McTamaney

So many stories vanish into the mists of time, even if they involve heroic people and events. History gets distilled into broad outlines and only some people have their deeds recorded often enough to get into the history books. Yet the lives of local men and women are usually as fascinating as major historical figures. They just don’t have enough witnesses – or influential witnesses – to their actions. One such man was Prince Danforth.

Prince Danforth (sometimes recorded as Danford) never wore a crown. He was likely given his name by his slave masters back in the 18th century when it seemed fashionable to assign classical names like Pompeii and Caesar and Queen and Prince to enslaved workers. Wealthy ladies and gentlemen believed it added a high tone to their manor houses to have high toned names involved in their domestic conversations. Whatever his birth name back in Africa, the man known in our old community, as Prince Danforth became a hero in the Revolutionary War, gained his freedom because of his heroism and went on to a post-war career as a successful farmer in New Windsor where he also received a veteran’s pension from the young federal government.

Prince Danforth was owned by James Clinton whose estate farm was in Little Britain. Census data reveals that he was born in Africa and we do not know his route from freedom to slavery and where and when he was first purchased, but New York City had an active slave market on the East River when Prince was a youth. The Clinton farm was large and so was the family. Originally from Northern Ireland, each generation had many children who married into New York’s colonial families.

Charles Clinton built the family farm in New Windsor and his son George became the governor of the colony of New York and then the first state governor after the war. James was George’s brother and they both served as officers in the Continental Army. Both were in the decisive Battle of Fort Montgomery on October 6, 1777 where James was wounded. His life was saved by his slave, Prince Danforth, who fought beside him as a member of the 2nd New York Regiment and stopped an English soldier from running Clinton through with a bayonet. Clinton freed Prince in gratitude. The Clinton family also gave Mr. Danforth farmland in Little Britain – 75 acres along what today is Toleman Road.

The family seems to have prospered. Their names appear in several historic documents through the years including tax roles, school district lists and church records. Prince Danforth married Peggy Robinson in Newburgh’s Associated Reformed Church in December of 1800. Back then, the little Reformed Presbyterian Church was at the foot of Renwick Street. Women’s lives were every bit as hard as men’s and Peggy died in the 1820’s. Prince remarried in 1828 in the Little Britain Presbyterian Church. A daughter, Catherine died as a toddler and her baptism and death are noted in the Little Britain church records. The Washingtonville Cemetery has records of the burials of two of his sons, Thomas and Peter, who lived through the years of the Civil War. By that time, the family name was more commonly spelled Danford.

One illustration of how Prince Danford’s life changed are two autographed documents that have survived the centuries. One is his application for a federal pension for his service in the Revolutionary War. His attorney, Newburgh’s Joseph Monell, wrote out his affidavit and it confirms that he served in the army for six years. Prince signs the paper, as so many of all our ancestors had to do, with an X. The words “his mark” then surround that handwritten X. For his service, Mr. Danford was awarded $8 per month starting in the year 1818. In addition to this old affidavit, the other official document relating to Mr. Danford was his military discharge, signed by George Washington himself. The elegant autograph of Washington contrasts to the simple mark of the old soldier who never had the chance to learn to write.

If there are Danfords still living in the area, it would be great to learn the continuing history of this New Windsor family and the slave who established their roots in New York.