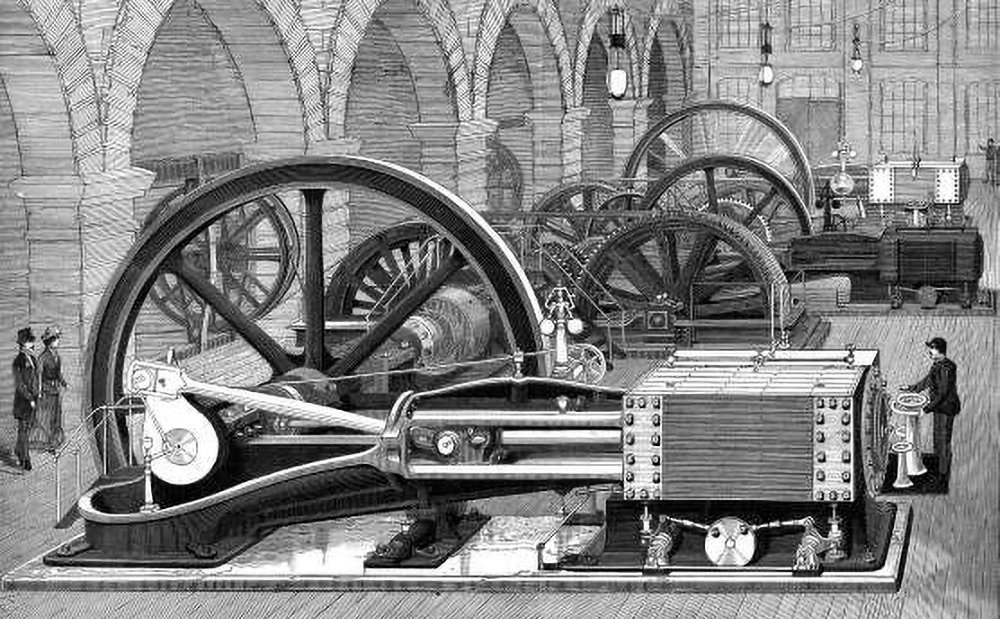

Below the Brooklyn Bridge in 1887, Newburgh steam engines powered the Brooklyn to Manhattan trolley system.

By Mary McTamaney

One hundred thirty-five years ago, the big doors opened at the Wright Engine Works on South Water Street and mechanics proudly pushed four massive steam engines out and onto waiting flatbed railroad cars for a trip by rail and river barge to Brooklyn, New York.

It wasn’t unusual for Newburghers to see lots of activity at the big and busy factory at the corner of Washington and Water Streets where over 200 machinists were employed making engines and engine parts during the “Age of Steam,” the late nineteenth century. The complex of machine shops, begun as the Washington Iron Works in the 1850’s, had been growing at that corner and provided many kinds of cast iron and steel machinery that America craved during its industrial revolution. The business greatly expanded in 1870 when it was purchased by engineer William Wright who had invented adaptations that transformed the efficiency of steam engines. Industrial scholars still call Mr. Wright one of the 19th century’s foremost engineers.

His revolutionary and efficient engines were just what was needed when the new Brooklyn Bridge had a crisis. The Brooklyn Bridge, constructed in 1883 as the first New York City river crossing, immediately exceeded all estimates for traffic usage. It was built before the automobile and, therefore, was designed to carry people on horseback, in carriages and on a street railway. The light rail system on the bridge was powered by an endless cable that ran from an engine house in Brooklyn over the railway track along the center lanes of the bridge and returned under the track from the Manhattan side. The original powerhouse for this cable railway proved too weak for the massive ridership taking the trolley and cars filled with people often stalled. A call went out in 1886 for engineers to design something better. Newburgh’s William Wright won that bid and built four engines in his Newburgh plant for a sum of $14,910. Mr. Wright and his crew constructed engines that could pull trains carrying 3 million passengers a month over the Brooklyn Bridge between what were then the separate cities of Brooklyn and New York.

The original trolley system engines had been housed in the bridge’s stone support arch but the strong new Newburgh engines required a special brick engine plant on the Brooklyn shore to house them. William Wright’s engine plan was innovative in that it allowed a clutching system to shift from one engine to another while the driving cable for the trolley was in motion. Engines could be shifted without losing any time and without the passengers being aware that their train was changing “drivers.” The biggest of the four Wright engines (625 horsepower) was used for rush hour commuter trains morning and evening and then gave way to smaller engines for lighter traffic times, allowing each to be rested and serviced. A sequence of several three-car trains picked up and delivered passengers to their trolley transfer stations on either shore so that passengers had very little waiting time.

It must have been amazing to step inside the brick engine house and watch William Wright’s steam engines in action. The largest one weighed over 50,000 pounds and had a flywheel 20 feet in diameter. The other three were of decreasing dimension but still giants of steam powered engineering. Hundreds of moving parts in each engine were crafted to precision specifications by the 19th century machinists Newburgh was famous for training. Steel, iron and wood were all hand-forged and carved to make every gear, grip and clutch ring ready to work for the trolley operating team waiting down in Brooklyn. One can imagine a team of skilled Newburgh mechanics travelling to the Brooklyn shore to instruct workers in that new brick engine house how to operate the innovative Wright engines that would provide better trolley service for several years to come. The journal Scientific American was impressed enough by the Wright system that it published a cover story about the revolutionary upgrade to the Brooklyn Bridge in its July 1888 issue.

catskillarchive.com/rrextra/bbcable.html.